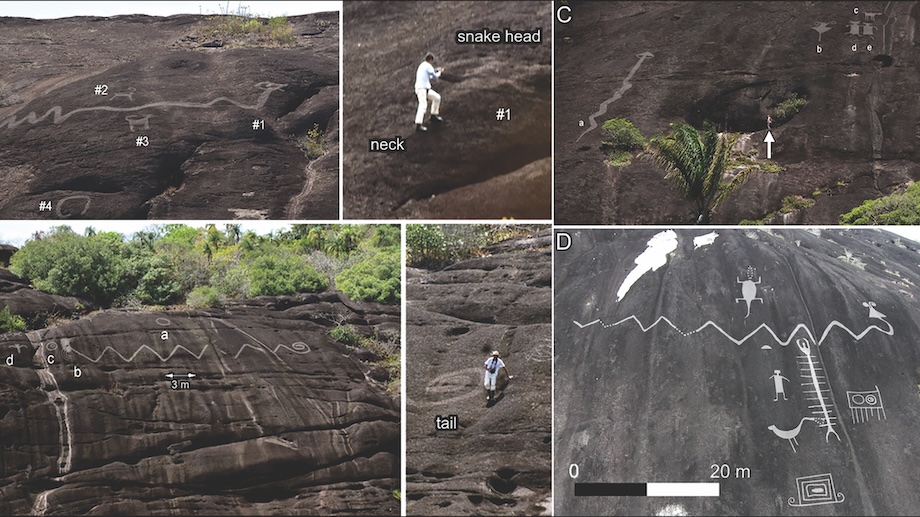

Archaeologists have fully mapped a series of ancient rock art in Venezuela and Colombia, including the world’s largest monumental engraving, using photography and drone footage.

The masterpieces, which feature both human and animal motifs, are prominently located along the Upper and Middle Orinoco River, which snakes through this region of South America. Researchers think the placement was intentional and was meant to be seen from a distance, since it was along the path of an important trade and travel route known as Atures Rapids, according to a study published Tuesday (June 4) in the journal Antiquity.

“One interpretation is that there was some aspect of territoriality at play,” lead author Philip Riris, a senior lecturer in archaeological and paleoenvironmental modeling at Bournemouth University in England, told Live Science. “It was a way of marking their territory and saying that this is our domain.”

Researchers are unsure of who created the massive engravings, the largest of which stretches 138 feet (42 meters) long. However, they do know that some of the subject matter, including a focus on snakes like boa constrictors and anacondas, “played an important role in the myths and beliefs of the local indigenous population,” according to a statement from Antiquity.

“Anacondas and boas were associated with the creator deity of some of the Indigenous groups living in the region,” Riris said. “Snakes also are known for being lethal; perhaps this was a way for them to warn outsiders that they were entering the domain of the snake.”

Related: Stunning rock art site reveals that humans settled the Colombian Amazon 13,000 years ago

One large snake motif, in particular, caught the attention of researchers as it resembled a similar drawing scrawled onto a piece of pottery unearthed in the area during a previous excavation. It includes horns, a spiral tail and a “well-defined zigzag” similar to the Cerro Palomazón snake depicted in the rock art, according to the study.

“A small urn recovered from a cave on one of the hillsides is decorated with a similar snake,” Riris said. “It’s possible that someone had copied what they were seeing on one of the walls. But my gut feeling is that whoever made [the urn] was a contemporary of whoever made the rock art.”

If that’s the case, based on the pottery, the rock art would be approximately 2,000 years old, according to the study.

Although most of the sites were previously known by researchers, they did discover several new locations during the mapping project.

“No where else in the world do we consistently see rock art of this size,” Riris said. “Elsewhere you might see large, one-off examples of rock art, but here we’ve found a concentration of sites that occur in regular intervals.”

The research team recently registered the sites with the Colombian and Venezuelan national heritage bodies and plans to work with local Indigenous groups to ensure that the rock art is protected, especially as the region becomes more open to tourism.

“It is badly in need of protection,” Riris said. “Our hope is that we can work together with local groups to protect and maintain the sites. We think that they would be best custodians for these sites.”